Designing your own entities with vertex arrays#

Introduction#

SFML provides simple classes for the most common 2D entities. And while more complex entities can easily be created from these building blocks, it isn't always the most efficient solution. For example, you'll reach the limits of your graphics card very quickly if you draw a large number of sprites. The reason is that performance depends in large part on the number of calls to the draw method. Indeed, each call involves setting a set of OpenGL states, resetting matrices, changing textures, etc. All of this is required even when simply drawing two triangles (a sprite). This is far from optimal for your graphics card: Today's GPUs are designed to process large batches of triangles, typically several thousand to millions.

To fill this gap, SFML provides a lower-level mechanism to draw things: Vertex arrays. As a matter of fact, vertex arrays are used internally by all other SFML classes. They allow for a more flexible definition of 2D entities, containing as many triangles as you need. They even allow drawing points or lines.

What is a vertex, and why are they always in arrays?#

A vertex is the smallest graphical entity that you can manipulate. In short, it is a graphical point: Naturally, it has a 2D position (x, y), but also a color, and a pair of texture coordinates. We'll go into the roles of these attributes later.

Vertices (plural of vertex) alone don't do much. They are always grouped into primitives: Points (1 vertex), lines (2 vertices), triangles (3 vertices) or quads (4 vertices). You can then combine multiple primitives together to create the final geometry of the entity.

Now you understand why we always talk about vertex arrays, and not vertices alone.

A simple vertex array#

Let's have a look at the SF::Vertex class now. It's simply a container which contains three public members and no functions besides its constructors. These constructors allow you to construct vertices from the set of attributes you care about -- you don't always need to color or texture your entity.

# create a new vertex

vertex = SF::Vertex.new

# set its position

vertex.position = SF.vector2(10, 50)

# set its color

vertex.color = SF::Color::Red

# set its texture coordinates

vertex.tex_coords = SF.vector2f(100, 100)

... or, using the correct constructor:

vertex = SF::Vertex.new({10, 50}, SF::Color::Red, {100, 100})

Now, let's define a primitive. Remember, a primitive consists of several vertices, therefore we need a vertex array. CrSFML provides a simple wrapper for this: SF::VertexArray. It provides the semantics of an array, and also stores the type of primitive its vertices define.

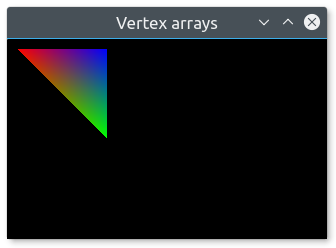

# create an array of 3 vertices that define a triangle primitive

triangle = SF::VertexArray.new(SF::Triangles, 3)

# define the positions and colors of the triangle's points

triangle[0] = SF::Vertex.new(SF.vector2(10, 10), SF::Color::Red)

triangle[1] = SF::Vertex.new(SF.vector2(100, 10), SF::Color::Blue)

triangle[2] = SF::Vertex.new(SF.vector2(100, 100), SF::Color::Green)

# no texture coordinates here, we'll see that later

Your triangle is ready and you can now draw it. Drawing a vertex array can be done similar to drawing any other CrSFML entity, by using the draw function:

window.draw(triangle)

You can see that the vertices' color is interpolated to fill the primitive. This is a nice way of creating gradients.

Note that you don't have to use the SF::VertexArray class. It's just defined for convenience, it's nothing more than an array along with a SF::PrimitiveType. If you need more flexibility, or a normal (or static) array, you can use your own storage. You must then use the overload of the draw function which takes an array of vertices and the primitive type.

vertices = [

SF::Vertex.new(...),

SF::Vertex.new(...),

]

window.draw(vertices, SF::Lines)

Primitive types#

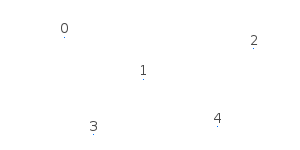

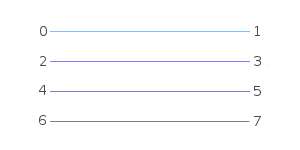

Let's pause for a while and see what kind of primitives you can create. As explained above, you can define the most basic 2D primitives: Point, line, triangle and quad (quad exists merely as a convenience, internally the graphics card breaks it into two triangles). There are also "chained" variants of these primitive types which allow for sharing of vertices among two consecutive primitives. This can be useful because consecutive primitives are often connected in some way.

Let's have a look at the full list:

| Primitive type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

SF::Points |

A set of unconnected points. These points have no thickness: They will always occupy a single pixel, regardless of the current transform and view. |  |

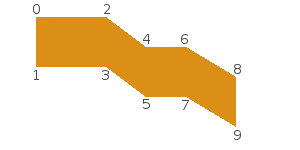

SF::Lines |

A set of unconnected lines. These lines have no thickness: They will always be one pixel wide, regardless of the current transform and view. |  |

SF::LinesStrip |

A set of connected lines. The end vertex of one line is used as the start vertex of the next one. |  |

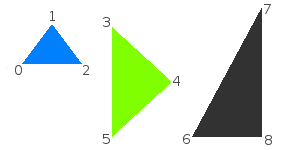

SF::Triangles |

A set of unconnected triangles. |  |

SF::TrianglesStrip |

A set of connected triangles. Each triangle shares its two last vertices with the next one. |  |

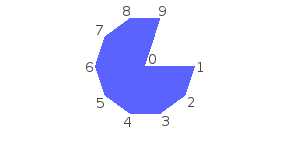

SF::TrianglesFan |

A set of triangles connected to a central point. The first vertex is the center, then each new vertex defines a new triangle, using the center and the previous vertex. |  |

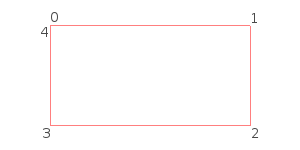

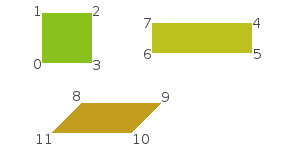

SF::Quads |

A set of unconnected quads. The 4 points of each quad must be defined consistently, either in clockwise or counter-clockwise order. |  |

Texturing#

Like other SFML entities, vertex arrays can also be textured. To do so, you'll need to manipulate the tex_coords attribute of the vertices. This attribute defines which pixel of the texture is mapped to the vertex.

# create a quad

quad = SF::VertexArray.new(SF::Quads, 4)

# define it as a rectangle, located at (10, 10) and with size 100x100

# define its texture area to be a 25x50 rectangle starting at (0, 0)

quad.append SF::Vertex.new({10, 10}, tex_coords: {0, 0})

quad.append SF::Vertex.new({110, 10}, tex_coords: {25, 0})

quad.append SF::Vertex.new({110, 110}, tex_coords: {25, 50})

quad.append SF::Vertex.new({10, 110}, tex_coords: {0, 50})

Texture coordinates are defined in pixels (just like the texture_rect of sprites and shapes). They are not normalized (between 0 and 1), as people who are used to OpenGL programming might expect.

Vertex arrays are low-level entities, they only deal with geometry and do not store additional attributes like a texture. To draw a vertex array with a texture, you must pass it directly to the draw method, through a SF::RenderStates object:

vertices = (...) # SF::VertexArray

texture = (...) # SF::Texture

# [...]

states = SF::RenderStates.new

states.texture = texture

window.draw(vertices, states)

Transforming a vertex array#

Transforming is similar to texturing. The transform is not stored in the vertex array, you must pass it to the draw method.

vertices = (...) # SF::VertexArray

transform = (...) # SF::Transform

# [...]

states = SF::RenderStates.new

states.transform = transform

window.draw(vertices, states)

To know more about transformations and the SF::Transform class, you can read the tutorial on transforming entities.

Creating an SFML-like entity#

Now that you know how to define your own textured/colored/transformed entity, wouldn't it be nice to wrap it in an SFML-style class? Fortunately, SFML makes this easy for you by providing the SF::Drawable module and SF::Transformable base class. These two classes are the base of the built-in SFML entities Sprite, Text and Shape.

SF::Drawable is an interface: it declares a single abstract method. Including sf::Drawable allows you to draw instances of your class the same way as SFML classes:

class MyEntity

include SF::Drawable

def draw(target : SF::RenderTarget, states : SF::RenderStates)

end

end

entity = MyEntity.new

window.draw(entity) # internally calls entity.draw

Subclassing the SF::Transformable class automatically adds the same transformation methods to your class as other CrSFML classes (position=, rotation=, move, scale, ...). You can learn more about this in the tutorial on transforming entities.

Using these two features and a vertex array (in this example we'll also add a texture), here is what a typical CrSFML-like graphical class would look like:

class MyEntity < SF::Transformable

include SF::Drawable

# add methods to play with the entity's geometry / colors / texturing...

def draw(target, states)

# apply the entity's transform -- combine it with the one that was passed by the caller

states.transform *= transform # transform() is defined by SF::Transformable

# apply the texture

states.texture = @texture

# you may also override states.shader or states.blend_mode if you want

# draw the vertex array

target.draw(@vertices, states)

end

end

You can then use this class as if it were a built-in CrSFML class:

entity = MyEntity.new

# you can transform it

entity.position = SF.vector2(10, 50)

entity.rotation = 45

# you can draw it

window.draw(entity)

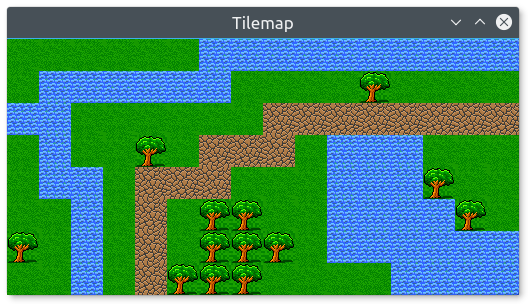

Example: tile map#

Relevant example: minesweeper

With what we've seen above, let's create a class that encapsulates a tile map. The whole map will be contained in a single vertex array, therefore it will be super fast to draw. Note that we can apply this strategy only if the whole tile set can fit into a single texture. Otherwise, we would have to use at least one vertex array per texture.

class TileMap < SF::Transformable

include SF::Drawable

def initialize(tileset, tile_size, tiles, width, height)

super

# load the tileset texture

@tileset = SF::Texture.from_file(tileset)

@vertices = SF::VertexArray.new(SF::Quads)

tiles_per_row = @tileset.size.x // tile_size.x

# populate the vertex array, with one quad per tile

(0...height).each do |y|

(0...width).each do |x|

# get the current tile number

tile_index = tiles[width*y + x]

# find its position in the tileset texture

tile_pos = SF.vector2(

tile_index % tiles_per_row,

tile_index // tiles_per_row

)

destination = SF.vector2(x, y)

# define its 4 corners and texture coordinates

{ {0, 0}, {1, 0}, {1, 1}, {0, 1} }.each do |delta|

@vertices.append SF::Vertex.new(

(destination + delta) * tile_size,

tex_coords: (tile_pos + delta) * tile_size

)

end

end

end

end

def draw(target, states)

# apply the transform

states.transform *= transform

# apply the tileset texture

states.texture = @tileset

# draw the vertex array

target.draw(@vertices, states)

end

end

And now, the application that uses it:

# create the window

window = SF::RenderWindow.new(SF::VideoMode.new(512, 256), "Tilemap")

# define the level with an array of tile indices

level = [

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,

0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0,

1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3,

0, 1, 0, 0, 2, 0, 3, 3, 3, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0,

0, 1, 1, 0, 3, 3, 3, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 0, 0,

0, 0, 1, 0, 3, 0, 2, 2, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 0,

2, 0, 1, 0, 3, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,

0, 0, 1, 0, 3, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1,

]

# create the tilemap from the level definition

map = TileMap.new("tileset.png", SF.vector2(32, 32), level, 16, 8)

# run the main loop

while window.open?

# handle events

while event = window.poll_event

if event.is_a? SF::Event::Closed

window.close

end

end

# draw the map

window.clear

window.draw(map)

window.display

end

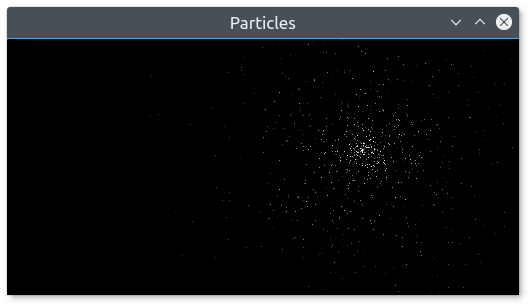

Example: particle system#

This second example implements another common entity: The particle system. This one is very simple, with no texture and as few parameters as possible. It demonstrates the use of the SF::Points primitive type with a dynamic vertex array which changes every frame.

struct Particle

def initialize(@velocity, @lifetime, @position)

@total_lifetime = @lifetime

end

property velocity : SF::Vector2f

property lifetime : SF::Time

property position : SF::Vector2f

getter total_lifetime : SF::Time

end

class ParticleSystem < SF::Transformable

include SF::Drawable

def initialize(@count : Int32)

super

@particles = [] of Particle

@emitter = SF::Vector2f.new(0.0f32, 0.0f32)

@random = Random.new

end

property emitter

def update(elapsed)

@particles.map! do |p|

# update the position of the particle

p.position += p.velocity * elapsed.as_seconds

# update the particle lifetime

p.lifetime -= elapsed

# if the particle is dead, remove it

if p.lifetime <= SF::Time::Zero

new_particle

else

p

end

end

if @particles.size < @count

@particles << new_particle

end

end

def draw(target, states)

vertices = @particles.map do |p|

# set the alpha (transparency) of the particle according to its lifetime

ratio = p.lifetime / p.total_lifetime

color = SF.color(255, 255, 255, (ratio * 255).to_u8)

SF::Vertex.new(p.position, color)

end

# apply the transform

states.transform *= transform

# draw the vertex array

target.draw(vertices, SF::Points, states)

end

private def new_particle

# give a random velocity and lifetime to the particle

angle = @random.rand(Math::PI * 2)

speed = @random.rand(50.0..100.0)

velocity = SF.vector2f(Math.cos(angle) * speed, Math.sin(angle) * speed)

lifetime = SF.seconds(@random.rand(1.0..3.0))

Particle.new(velocity, lifetime, @emitter)

end

end

And a little demo that uses it:

# create the window

window = SF::RenderWindow.new(SF::VideoMode.new(800, 600), "Particles")

# create the particle system

particles = ParticleSystem.new(1000)

# create a clock to track the elapsed time

clock = SF::Clock.new

# run the main loop

while window.open?

# handle events

while event = window.poll_event

if event.is_a? SF::Event::Closed

window.close

end

end

# make the particle system emitter follow the mouse

mouse = SF::Mouse.get_position(window)

particles.emitter = window.map_pixel_to_coords(mouse)

# update it

elapsed = clock.restart

particles.update(elapsed)

# draw it

window.clear

window.draw(particles)

window.display

end